But I read the living heck out of the books, and while this wasn't the intent of the author, the lessons I took from his stories planted the seeds of skepticism in my brain.

I can't recall whether any of my choral groups performed this version of the hymn or not, but the John Rutter recording seemed the most familiar (and least cheesy) of those I could find on YouTube.

(Lyrics - and music - are available here.)

Songs like this one, which take the sense of wonder we all feel when we look at the world around us, and attribute that wonder to a concept of God are pretty common, across many cultures. The words bugged me when I was younger, because they focused so heavily on the pretty and charming side of nature, while completely ignoring the inherent danger. That seemed creepy and Orwellian to me, even then.

Nature's red in tooth and claw seems to be as apt a thing to attribute to an omnipotent being as each little flow'r that opens or each little bird that sings. And if we were going to give God credit for all of the sweet, pretty, and delightful things in the world He made, shouldn't he also get credit for making the violent, brutal, and dangerous things, too? When I questioned that, I got uncomfortable and tortured answers, which seemed to indicate that my elders were uneasy with the implication that an omnipotent God should also be held to account for what we call "evil."

It would take me about thirty years to process the cognitive dissonance that this produced. For several years during college, I was obsessed with the musical Jesus Christ Superstar in part because the character of Judas does what he does out of a sense of duty. He thinks he is "the good guy" when he goes to the Pharisees to turn Jesus in; and when he realizes that he was manipulated into doing an "evil" deed as part of God's plan, he is devastated:

Christ!

I know you can't hear me

But I only did what you wanted me to

Christ!

I'd sell out the nation

For I have been saddled

With the murder of you

God I'll never know

Why you chose me for your crime

Your foul bloody crime

You, you have murdered me

taken from: Jesus Christ Superstar - Judas' Death Lyrics | MetroLyrics

Considering things from Judas's point of view is not generally approved of by the elders, either, by the way. They will remind you (with no sense of irony whatsoever) that Jesus Christ Superstar is fictional. But if you set aside the interesting puzzle of how much of the Jesus story is literally true, you will notice that they are still attempting to pull that sleight of hand wherein God gets all the credit and glory for everything good. The point of this trick is to shift anything evil - even if it was His idea, and necessary to His plot - onto you.

None of that epic philosophical struggle shows up in James Herriot's very popular books about a Yorkshire veterinarian in the 1930s. Instead, you get a lot of amusing stories that reveal the character of the small towns and farms of the English countryside. Herriot certainly doesn't set out to undermine God, here; in fact, I rather think that he would consider the themes in his stories to revolve around how humans misunderstand nature.

Selecting the lyric of that hymn for his title would indicate that he, too, attributes all of the goodness he sees around him to God. If anything, I think his intent was to bring out the good and the noble side of the subjects of his tales, and show that much of what people consider "evil" is better treated as ignorance or fear of the unknown, and that knowing more gives you the power to do more good. I still embrace that hopeful theme.

|

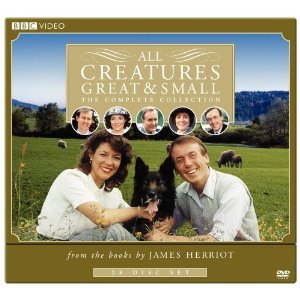

| The TV series I always wanted to watch... |

One might have a calf with an easily treated calcium deficiency, but he would treat it with absurd tinctures and potions to avoid a veterinary bill. That farmer would finally give in and call Dr. Herriot, only to attribute the miraculous recovery to whatever arcane ritual had been performed before the good Doctor's arrival.

Another would call the vet right away only to find a deadly and un-treatable condition that required Herriot to put down a "perfectly good animal."

And then - possibly the worst feeling - there would be a case so difficult and mysterious that even after Dr. Herriot thought he would lose the animal. Yet, when he solved the mystery and miraculously saved the animal, the farmer would shrug, unimpressed, and mumble something like, "That's what ye charge so much for, innit?"

Sharing Herriot's affable frustrations over the years primed me to recognize the human animal's susceptibility to fooling himself. Failing to spot the holes in the stories we tell ourselves is widespread, and it's rare indeed that anyone responds well to having those holes pointed out.

I get why people respond so poorly and unpredictably to having their worldview challenged. I get why they would be suspicious of someone trying to change the way they think. It can be terrifying to realize that the core assumptions you've made about the nature of the universe and the benevolence of the God you worship have some internal inconsistencies. Most people who realize that their myths aren't true are going to recoil in horror.

Some may face the dilemma that fictional Judas faced; a deep sense of guilt for acting in a way they thought was good. Some may feel less noble, and simply double down to save face. And if you're the one pointing out the dangerous flaw that threatens their sense of self, their integrity, their nobility? Well, you're probably going to take the brunt of their reaction.

Don't feel bad - that's just nature demonstrating how wise and wonderful it is.

No comments:

Post a Comment